Hello dears! Here’s what I’ve got this year: vitality, oddness, fury, pleasure, the continued beating of our shared hearts. No song-by-song story this time— the slow December drafting/chiseling time I’d given over to this writing in years past was spent, instead, grading my students’ wonderful work— but I hope you love wandering through the music with me. A few from 2020 that caught up to me late (Roisin Murphy, Arbor Labor Union, ChocQuibTown, mid-century Indian violin), many songs that were gifts from particular friends and particular moments, a few hours of good life. Enjoy!

Category Archives: music

The Fourteen Best Things on the Internet: May 2020

Hey dears, long time coming: a post of the podcasts, essays, music videos, beautiful internet jetsam/takes that I’ve been thinking about and wrestling with since shelter-in-place began. As I noted when I started this post series, it’s way too easy for me to retweet-broadcast-resonate with something I read online without actually digesting it, learning from it, or responding fully to it; this series is my attempt to do more justice to challenging thinking, human complexity, and good art I encounter online. Many of these articles are old-ish; I grind slowly. Look for another post like this one soon.

*

1. Journalist Connie Walker’s CBC limited series Missing & Murdered: Finding Cleo is the best podcast I’ve ever heard. Finding Cleo brings historical research, bloodhound sleuthing, structural political analysis, and shattering emotional power to a story of a missing Cree girl: Cleopatra Semaganis Nicotine, forcibly taken from her mother in Little Pine, Saskatchewan, and forced into foster care by white social workers in Canada’s “sixties sweep” of Indigenous children and teens. Cleo was separated from her siblings, given a new name, adopted into the United States, and then– as her siblings heard secondhand– died under mysterious circumstances. But US and Canadian governments offered the family no further information on her short life: no death certificate, no information on her series of foster and adoptive families, and no information on where Cleo was buried. Finding Cleo is the attempt by Walker (also a Cree woman from Saskatchewan) to find answers for the Semaganis siblings on what happened to Cleo. Thank you to Bri for telling me about it.

1. Journalist Connie Walker’s CBC limited series Missing & Murdered: Finding Cleo is the best podcast I’ve ever heard. Finding Cleo brings historical research, bloodhound sleuthing, structural political analysis, and shattering emotional power to a story of a missing Cree girl: Cleopatra Semaganis Nicotine, forcibly taken from her mother in Little Pine, Saskatchewan, and forced into foster care by white social workers in Canada’s “sixties sweep” of Indigenous children and teens. Cleo was separated from her siblings, given a new name, adopted into the United States, and then– as her siblings heard secondhand– died under mysterious circumstances. But US and Canadian governments offered the family no further information on her short life: no death certificate, no information on her series of foster and adoptive families, and no information on where Cleo was buried. Finding Cleo is the attempt by Walker (also a Cree woman from Saskatchewan) to find answers for the Semaganis siblings on what happened to Cleo. Thank you to Bri for telling me about it.

2. Bernard Avishai, “By Barring Two Congresswomen, Trump and Netanhayu Set a Trap for Democrats.” This take is seven months old, but Avishai’s take on authoritarian populism, American Jewish politics, B.D.S., and Trump’s relationship with Netanhayu has stuck with me. Avishai– an Israeli liberal who seems to have moved toward supporting a one-state “confederation” of Israel and Palestine and a right of return for all Palestinian refugees– writes of Trump’s long-term plan to paint Democrats as anti-Semitic and Israel and the United States as partners: partners not around “shared democratic values” and civil rights for oppressed minorities, but around “hard nationalism,” military might, and “traditional, populist, wall-building” majoritarian politics. Last summer, Trump publicly pushed Netanyahu to take the unprecedented step of banning Democratic Congresswomen Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, both Muslim, from visiting Israel. Netanyahu’s government, which has passed legislation barring supporters of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (B.D.S.) from entry to Israel, was willing to comply. Both Omar and Tlaib have expressed qualified support for B.D.S., which calls for a boycott of “Israel’s apartheid regime, complicit Israeli sporting, cultural and academic institutions,” and “all Israeli and international companies engaged in violations of Palestinian human rights.”

2. Bernard Avishai, “By Barring Two Congresswomen, Trump and Netanhayu Set a Trap for Democrats.” This take is seven months old, but Avishai’s take on authoritarian populism, American Jewish politics, B.D.S., and Trump’s relationship with Netanhayu has stuck with me. Avishai– an Israeli liberal who seems to have moved toward supporting a one-state “confederation” of Israel and Palestine and a right of return for all Palestinian refugees– writes of Trump’s long-term plan to paint Democrats as anti-Semitic and Israel and the United States as partners: partners not around “shared democratic values” and civil rights for oppressed minorities, but around “hard nationalism,” military might, and “traditional, populist, wall-building” majoritarian politics. Last summer, Trump publicly pushed Netanyahu to take the unprecedented step of banning Democratic Congresswomen Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, both Muslim, from visiting Israel. Netanyahu’s government, which has passed legislation barring supporters of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (B.D.S.) from entry to Israel, was willing to comply. Both Omar and Tlaib have expressed qualified support for B.D.S., which calls for a boycott of “Israel’s apartheid regime, complicit Israeli sporting, cultural and academic institutions,” and “all Israeli and international companies engaged in violations of Palestinian human rights.”

What does Avishai think of B.D.S.? “It has never been clear,” Avishai points out, “whether the external pressure that the leaders of the movement are trying to mobilize is aimed at ending the occupation or at ending the state of Israel itself.” B.D.S., Avishai concedes, makes a clear moral point: the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories is cruel, authoritarian, and hardening by the year; Israel remains in the control of fundamentalists and it continues to deny Palestinian national and civil rights. Progressive Americans, including Jews, increasingly believe that Palestinian refugees deserve a right of return to a secularized and reconstituted nation; that Israel’s current policy represents “a civil-rights violation on the world stage”; and that “B.D.S., for its part, seems… a reasonable, nonviolent way to confront it.” Through a B.D.S. campaign, “[y]ou boycott Israeli institutions and agitate for disinvestment from Israeli businesses, or from global companies that partner with them; you agitate to sanction Israeli government officials, and threaten to take them to the International Criminal Court,” making Israelis “hurt until they get the message.”

What does Avishai think of B.D.S.? “It has never been clear,” Avishai points out, “whether the external pressure that the leaders of the movement are trying to mobilize is aimed at ending the occupation or at ending the state of Israel itself.” B.D.S., Avishai concedes, makes a clear moral point: the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories is cruel, authoritarian, and hardening by the year; Israel remains in the control of fundamentalists and it continues to deny Palestinian national and civil rights. Progressive Americans, including Jews, increasingly believe that Palestinian refugees deserve a right of return to a secularized and reconstituted nation; that Israel’s current policy represents “a civil-rights violation on the world stage”; and that “B.D.S., for its part, seems… a reasonable, nonviolent way to confront it.” Through a B.D.S. campaign, “[y]ou boycott Israeli institutions and agitate for disinvestment from Israeli businesses, or from global companies that partner with them; you agitate to sanction Israeli government officials, and threaten to take them to the International Criminal Court,” making Israelis “hurt until they get the message.”

But, Avishai writes, “B.D.S. is an unexamined, contradictory bundle, because boycott, divestment, and sanctions are three very different things, hurting very different slices of Israeli society.” (This comment echoes Noam Chomsky’s sober criticism of B.D.S.’s aims, given while also affirming its goals: boycott, divestment, and sanctions are divergent strategies with differing likelihoods of success.) If Omar and Tlaib had been permitted to visit Israel, Avishai imagines, they would have seen a nation whose internal divisions seem “utterly familiar”: a “comparatively élite, cosmopolitan—and frustrated—Tel Aviv coast up against poor, pietistic Jerusalem and the rest of the country.” This, Avishai seems to believe, would have shown them the nuances of Israel’s domestic politics and thus softened their support for B.D.S.

There are better tools than B.D.S., Avishai believes, to economically challenge injustice inside Israel: “One can imagine governments sanctioning Israeli settlement policies, much like George H. W. Bush did, in 1991, when he warned that he would deduct any sum that Israel spent on settlements from American loan guarantees. One can imagine international organizations setting telecommunications standards sanctioning Israelis for hogging bandwidth from Palestinian telecom companies.” But a boycott, Avishai argues, would undermine, not empower, Israel’s progressive constituencies and leadership: “[B]oycott the Hebrew University and you boycott scholars trying to bridge the studies of the Holocaust and the Nakba. Boycott Israeli chipmakers and you boycott companies setting up research offices in Palestine.” Instead, Avishai believes, American progressives need to better educate themselves on, and work to empower, their Israeli counterparts. “In both places,” he admits, “it will be a long haul.”

Left out of Avishai’s analysis is a look at support for B.D.S. among Israelis sympathetic to Palestinian demands for justice, or a cost-benefit analysis of politically isolating Israel’s current government (and possibly empowering Netanhayu’s nationalist us-versus-a-threatening-world rhetoric) as a consciousness-raising strategy to educate and mobilize fence-sitting moderates.

*

3. When something is neither blessed nor cursed, it’s blursed:

*

4. How can municipal governments make their police forces less violent, and what policy changes can activists demand that most effectively reduce state violence in their communities? I first heard about scholar and policy analyst Samuel Sinyangwe from an admiring tweet by DeRay Mckesson; he’s an insightful presence who thinks empirically and intersectionally about justice issues. Here’s a thread of his research-based solutions to police violence. (Kudos to him too for updating his conclusions slightly since he first posted his research on this topic.)

4. How can municipal governments make their police forces less violent, and what policy changes can activists demand that most effectively reduce state violence in their communities? I first heard about scholar and policy analyst Samuel Sinyangwe from an admiring tweet by DeRay Mckesson; he’s an insightful presence who thinks empirically and intersectionally about justice issues. Here’s a thread of his research-based solutions to police violence. (Kudos to him too for updating his conclusions slightly since he first posted his research on this topic.)

*

5. Troy Vettese, “Sexism in the Academy.” It’s not getting better. The representation of women in academia shrinks the higher you go; the percentage of female full professors in the US is just 32%, and there are two tenured men for every tenured man. Women have been the majority of undergrads for decades– it’s not that the pipeline hasn’t let them through yet. Male scholars “are more zealous about safeguarding time for research, they are skeptical of women’s competence, and they endanger and demoralize female scholars through sexual harassment.” Undoing sexism in the academy, Vettese writes, requires confronting a “vast ramshackle machinery” that pushes men up the ivory tower while pushing women out.

5. Troy Vettese, “Sexism in the Academy.” It’s not getting better. The representation of women in academia shrinks the higher you go; the percentage of female full professors in the US is just 32%, and there are two tenured men for every tenured man. Women have been the majority of undergrads for decades– it’s not that the pipeline hasn’t let them through yet. Male scholars “are more zealous about safeguarding time for research, they are skeptical of women’s competence, and they endanger and demoralize female scholars through sexual harassment.” Undoing sexism in the academy, Vettese writes, requires confronting a “vast ramshackle machinery” that pushes men up the ivory tower while pushing women out.

What does this this machinery consist of? First, a skepticism of women’s talent at all levels of mentorship: there is “a widespread assumption that only men can be brilliant.” This toxic belief is especially prevalent in elite life science labs (where male PIs ensure that women make up only 31% of their postdoc workforce), but it shows up as well in fields as diverse as literature, musical composition, and philosophy. In all sciences, women lose time “proving a result again” to skeptical supervisors. (The data are inarguable: female scholars as a whole are asked to spend 9-12% more time making revisions when preparing work for publication.) In the world of grants, the gender gap in awards is about 7 percent and “when women are successful in their grant applications, they usually receive less funding, about eighty cents to a man’s dollar.”

Second, the widespread and naked ugliness of sexual harassment: “women often have to change field sites, topics, or even departments to avoid predatory men, diversions that eat up precious time for scholarship, not to mention the stress of such experiences.” One fifth to one half of female postgrads experience sexual harassment from a colleague, mentor, or supervisor.

Third, the power of citation. This is pervasive and pernicious. It shows up as skepticism of entire fields of study, where “[m]ethods pioneered by female scholars, such as feminist critiques of science or constructivism in international relations, are seen by male peers as ‘soft,’ and these peers are less likely to cite works employing such approaches.” It also shows up in male self-citation: “[a] male scholar is nearly twice as likely to cite his previous work [accounting for a tenth of all citations] than a female peer is to cite her own… Self-citation builds up the base of a paper’s citation count, leading other scholars to cite that paper at a rate of about four new citations for every self-citation.” This might seem like harmless ego-stroking by male scholars, but the simple numerical weight of citation matters for tenure. And unsurprisingly, men are overall less likely to cite women: “In one study of economics articles, men were half as likely as women to cite the work of female scholars, while women manifested no such bias.”

Fourth, let’s not forget students. Course evaluations are critical for advancement to tenure, and male students overwhelmingly privilege male faculty and peers. Male students expect maternally-coded care from female professors: “students tend to evaluate a female instructor according to how well prepared she is in the classroom, which forces women to spend significantly more time preparing than men… By comparison, students expected their male teachers to be charismatic and knowledgeable, traits that require much less preparation to perform. Again, the widespread expectation held by boys and men is that only boys and men can be brilliant.” This, of course, trickles down to peer relationships among students as well: “In a study of three US undergraduate biology courses, students voted for their most intelligent peer during the semester. Generally the women gave a very slight edge to other women in their voting, but men favored other men by a nineteenfold margin.” (My emphasis.)

Fifth (for fifth column), husbands and male partners of female academics. Men are much, much less likely to sacrifice a work opportunity or research time, to take on childcare, or to explicitly value the career of a female partner than vice versa. “A woman was much more likely to say that her career was as important as her partner’s. This was true a majority of the time, even if women were making more money than their male partners, while the obverse was much less common.”

Finally, the simple fact that academic advancement is often conducted informally and secretively. A system that permits men to advance the colleagues in their networks they most admire, without any public or standard evaluation process, will inevitably favor other men. Most academic job applications are noncompetitive or unpublicized. “The problem in the academy comes down to men’s relative advantage over women, rather than any absolute gains women may make.”

Vettese examines the effects of having women in positions of academic leadership. It’s indispensable, he concludes, “though not a complete solution.” When women became chairs, deans, or central administrators, writes one scholar, “a woman’s holding of this position would devalue or minimize it somewhat, casting it into the service mode, not the power mode. We heard this comment so frequently across all disciplines that we finally named it gender devaluation.” Further, “When women step in to help other women, such as when they act as ‘diversity czars’ in the US to ensure hiring and tenure reviews are equitable, they risk provoking a backlash from men... The high risks and scanty rewards of feminist solidarity are likely why the levels of politicization among female faculty tend to be surprisingly low. Many scholars seem to see the burdens they carry as the result of their own choices or the behavior of individual misogynistic men, rather than as structured by a larger patriarchal system.”

What current models exist for alternatives? Vettese cites Turkey. At least before the AKP ascended to power, “the Turkish academy employed proportionately almost twice as many female full professors as the EU average.” This is not because Turkey is less sexist than other countries. Rather, it’s due to a mix of factors: first, the country’s universities have strict, open, and competitive guidelines regulating the appointment of professors. Turkey’s universities also mandate “that all competitions must be announced in a major newspaper, and applicants are judged on the basis of a defined portfolio.” An academic career is also considered a “safe” choice for Turkish women, serving as an outlet for “the career aspirations of bourgeois women denied other options.” Of course, as elsewhere in the world, bourgeois Turkish women’s advancement is dependent on cheap women’s labor: “servants [who] relieve female professors of the burdens of cooking, cleaning, and child care.”

So what can be done? Vettese is blunt: new rules at all levels of the academy. The struggle against sexism in the academy is zero-sum– women’s advancement depends on power being taken from men– and so, Vettese argues, strong rules to destroy informal sexist networks of advancement are the only way to break men’s strong resistance. “Courses on women’s history or feminist philosophy should be mandatory. Until male students are taught to reflect upon their biases, they should be barred from evaluating peers and teachers. Similarly, male scholars’ power to evaluate female peers and students should also be restrained. At the very least, mixed panels for a scholar’s career assessments ought to be required… [R]ising quotas should be in place for hiring more female scholars in all stages of the tenure track.” Universities should make salaries public to help ensure pay equity, and they should publish “referees’ reports to journal editors to reduce vitriol and bias. Spousal-hire programs could persuade more husbands to follow their wives.”

Further, “[f]ree state- or university-run crèches, day care centers, after-school activities, and canteens” would be a valuable partial remedy to theunequal distribution of social labor. A shortened workweek would also be an across-the-board gift: “Reducing the workweek to thirty-five hours would allow those within the academy time to enjoy their intellectual endeavors and carry out social reproduction, while spreading work among more colleagues and absorbing the glut of underemployed doctoral graduates — a group that is composed mostly of women because they drop out of the academy at every career milestone at twice the rate men do, according to one study of women in the sciences.”

This is a matter of individual suffering, not just institutional self-impoverishment: “like all scholars, women eschew potential riches to seek their intellectual fortune, motivated by a passion to learn and teach. That so many are forced to relinquish this goal because of condescending or lewd supervisors, selfish spouses, smug students, and prejudiced hiring committees is in every case a personal tragedy of an unfulfilled life.” Thanks to Lindsay Turner for tweeting about this article and letting me know it existed.

*

6. Robyn’s video for “Ever Again,” a Labyrinth re-enchantment: you know that kind of desire where you want someone and want to be them at once?

*

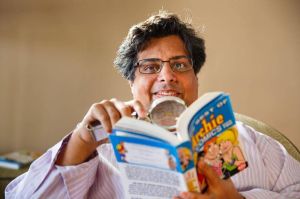

7. Jeet Heer, “Leftists Shouldn’t Go on Tucker Carlson.” One of my beloved “irresponsible Twitter clowns” and a fan of my bottom-dollar favorite science fiction author, Heer is also a serious-minded and big-picture lefty national-affairs writer. And, since I once semi-admiringly shared here a conservative anti-war-machine essay that Carlson wrote, I thought I owed some attention to Heer’s argument that leftists shouldn’t grant Carlson a platform, or accept a space on his Fox News show. Heer argues that it’s still sometimes worthwhile for leftists to go on Fox News generally: for politicians and candidates, “politics inevitably involves convincing those outside the fold.” But for activists and writers, “there’s a delicate balance to strike between getting the message out while also making sure that bigotry isn’t normalized.” Carlson is crafty, “as insidious as he is odious,” and is skilled at channeling anti-war and grassroots anti-business rhetoric to serve an isolationist politics and an ideological hatred of immigrants and of “coastal elites.” On the other hand, CNN and MSNBC are hostile to anti-war leftists; on which other cable show can you criticize hawks, or to argue against intervention in Syria or Venezuela? How can you not “agree with someone [such as Carlson] in a way that lends itself to bigotry”? It’s a complex dance, but Heer insists that leftists should engage it carefully, lest they build the platform of a very dangerous figure, a true American proto-fascist.

7. Jeet Heer, “Leftists Shouldn’t Go on Tucker Carlson.” One of my beloved “irresponsible Twitter clowns” and a fan of my bottom-dollar favorite science fiction author, Heer is also a serious-minded and big-picture lefty national-affairs writer. And, since I once semi-admiringly shared here a conservative anti-war-machine essay that Carlson wrote, I thought I owed some attention to Heer’s argument that leftists shouldn’t grant Carlson a platform, or accept a space on his Fox News show. Heer argues that it’s still sometimes worthwhile for leftists to go on Fox News generally: for politicians and candidates, “politics inevitably involves convincing those outside the fold.” But for activists and writers, “there’s a delicate balance to strike between getting the message out while also making sure that bigotry isn’t normalized.” Carlson is crafty, “as insidious as he is odious,” and is skilled at channeling anti-war and grassroots anti-business rhetoric to serve an isolationist politics and an ideological hatred of immigrants and of “coastal elites.” On the other hand, CNN and MSNBC are hostile to anti-war leftists; on which other cable show can you criticize hawks, or to argue against intervention in Syria or Venezuela? How can you not “agree with someone [such as Carlson] in a way that lends itself to bigotry”? It’s a complex dance, but Heer insists that leftists should engage it carefully, lest they build the platform of a very dangerous figure, a true American proto-fascist.

*

8. Jasper Bernes, “Between the Devil and the Green New Deal.” Bernes takes a hard look at the supply chain of supposedly renewable energy: the fossil fuels needed for the steel and concrete of new high-speed rail, new “green” power infrastructure, etc., yes, but also the costs of extracting copper, selenium, and lots and lots and lots of lithium for electric cars, solar panels, and wind turbines. These elements are rare– they’re as subject to exhaustion as fossil fuels– and they’re also incredibly toxic to mine and process. “In exchange for these terrestrial treasures—used to power trains and ships and factories—a whole class of people is thrown into the pits.” Bernes is skeptical that the Green New Deal’s target– zero emissions in the US by 2030– can be met: throwing open the doors to industry to meet this goal would begin “a race… likely to be ugly, in more ways than one, as slipshod producers scramble to cash in on the price bonanza, cutting every corner and setting up mines that are dangerous, unhealthy, and not particularly green.” And to build this green infrastructure, what would power the mining equipment, the container ships, the construction machinery, and the remediation needed for cleaning up the radioactive tailings ponds the mines leave behind? Probably fossil fuels; maybe biofuels, but growing these “requires land otherwise devoted to crops, or carbon-absorbing wilderness.” And reducing emissions, while still using pesticides and further extending human development into animal habitat, will do little to slow rates of species loss. The growth demanded by capitalism is going to be fatal for our species. “There is no solution to the climate crisis,” Bernes flatly says, “which leaves capitalism’s compulsions to growth intact.”

But could the Green New Deal be implemented to begin with? To force a transition to green power would “require far greater power over the behavior of capitalists than the New Deal ever mustered,” especially now that, thanks to fracking, the price of oil is going to stay low. Renewables are getting cheaper. But to be a good investment, renewables will need to be not slightly cheaper than fossil fuels, but vastly cheaper, since there are trillions of dollars sunk into fossil fuel infrastructure, “and the owners of those investments will invariably choose to recoup some of that investment rather than none of it.” There is $50 trillion worth of oil still in the ground, and forcing investors to leave it there will be an unbelievable battle: “If you propose to wipe out $50 trillion, one-sixth of the wealth on the planet, equal to two-thirds of global GDP, you should expect the owners of that wealth to fight you with everything they have, which is more or less everything.” They will fight not because they’re villains, but because they’re helpless: “Even if these owners wanted to spare us the drowned cities and billion migrants of 2070, they could not. They would be undersold and bankrupted by others. Their hands are tied, their choices constrained, by the fact that they must sell at the prevailing rate or perish.”

Some see advocacy for the Green New Deal as a transition (never named as such) to a socialist economy. Bernes is skeptical that the capitalist institutions that the Green New Deal would build up would be open to a sudden change of plans: “Beware that, in pursuit of the transitional program, you do not build up the forces of your future enemy.” And the Green New Deal’s core assumption– that its world “is this world but better—this world but with zero emissions, universal health care, and free college”– is an impossible one.

So what, besides the nightmares of geoengineering or the fortressing of the wealthy against the tides of the poor, is possible? “A revolution that had as its aim the flourishing of all human life would certainly mean immediate decarbonization, a rapid decrease in energy use for those in the industrialized global north, no more cement, very little steel, almost no air travel, walkable human settlements, passive heating and cooling, a total transformation of agriculture, and a diminishment of animal pasture by an order of magnitude at least.” But this wouldn’t be a gray, bleak world. “An emancipated society, in which no one can force another into work for reasons of property, could offer joy, meaning, freedom, satisfaction, and even a sort of abundance. We can easily have enough of what matters—conserving energy and other resources for food, shelter, and medicine. As is obvious to anyone who spends a good thirty seconds really looking, half of what surrounds us in capitalism is needless waste.” Bernes would rather work for this than for what he believes the Green New Deal is: a fantasy.

*

9. Cecil Taylor, “Spring of Two Blue-J’s (Pt 1).” What a holy and electrifying racket!

*

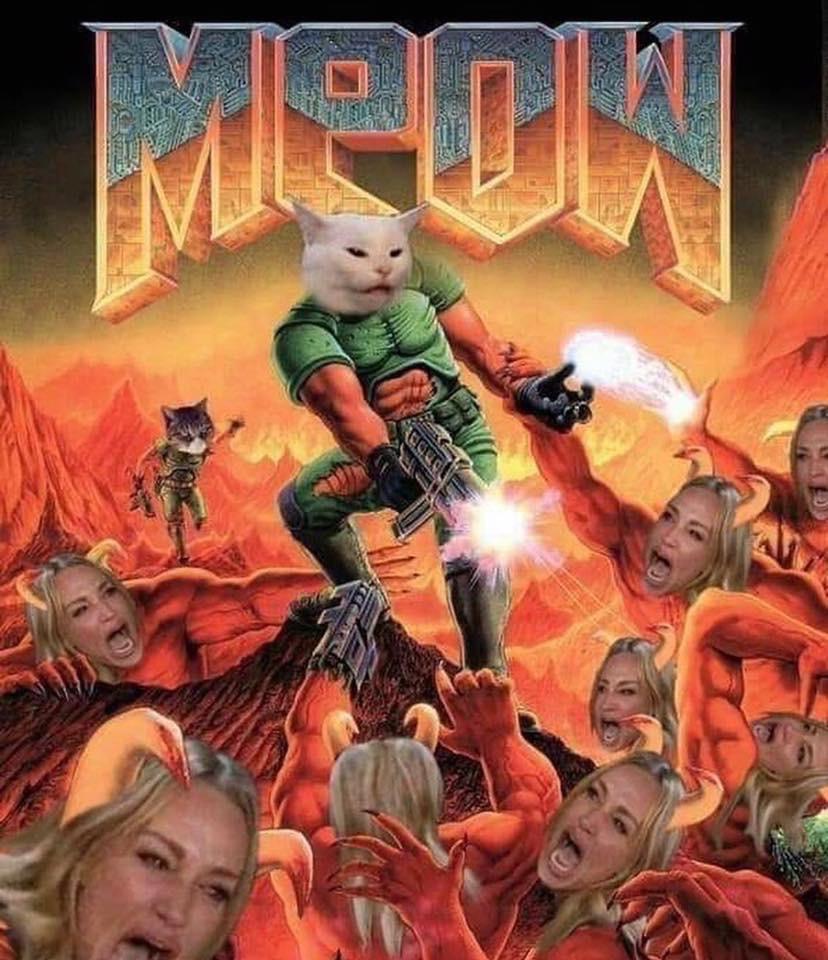

10. Meme upon meme upon meme: source.

*

11. Always read Kary Wayson’s poems:

https://therumpus.net/2019/12/rumpus-original-poetry-three-poems-by-kary-wayson/

*

12. Isaac Ariail Reed, “The King’s Two Bodies and the Crisis of Liberal Modernity.” What is it, exactly, that’s propelling right-wing populism and revealing the tattering of the social fabric of western democracies? We’re economically exploited and spiritually alienated, yes, but Reed’s answer to this urgent question doesn’t draw mostly from (say) Marx’s understandings of the dynamics of capitalism, nor from Weber’s theories of modernity’s disenchantment and its differentiation of the individual (into a being of many communities, spheres, and sources of meaning). Instead, Reed focuses on the ongoing relevance of “ancient human tendency to imagine that in the leader is contained the community.” Kingship in medieval times stretched far beyond the life and death of a given monarch; the “second body” of the king was seen as present in statecraft, commerce, ideology. Medieval lives were constituted by a felt relationship to “king and country.” When mourners cried, “the king is dead, long live the king!” they were embracing the presence of kingship beyond the life of an individual monarch.

12. Isaac Ariail Reed, “The King’s Two Bodies and the Crisis of Liberal Modernity.” What is it, exactly, that’s propelling right-wing populism and revealing the tattering of the social fabric of western democracies? We’re economically exploited and spiritually alienated, yes, but Reed’s answer to this urgent question doesn’t draw mostly from (say) Marx’s understandings of the dynamics of capitalism, nor from Weber’s theories of modernity’s disenchantment and its differentiation of the individual (into a being of many communities, spheres, and sources of meaning). Instead, Reed focuses on the ongoing relevance of “ancient human tendency to imagine that in the leader is contained the community.” Kingship in medieval times stretched far beyond the life and death of a given monarch; the “second body” of the king was seen as present in statecraft, commerce, ideology. Medieval lives were constituted by a felt relationship to “king and country.” When mourners cried, “the king is dead, long live the king!” they were embracing the presence of kingship beyond the life of an individual monarch.

This myth was rewoven in modernity. The American and French revolutions of the 18th century were fought against the king and on behalf of the people, a new binding and mystical body. But who, exactly, got to be people, and what is their common good? The longing of the modern era is for a good society where “every individual has two bodies… [and is] imbued with the dignitas that formerly accompanied the king.” But this longing has never been made real in a modern liberal democracy: slavery and colonial violence underlies the modern state. And it’s no accident that in modernity racism and ethnic hatred became increasingly potent as instruments of “denying access to democratic politics,” since the question of delegation of political agency in the new states was foundational to these states’ senses of themselves. “To secure delegation in a world in which every citizen is a king in his own castle, the distribution of personhood became fiercely, violently strict about its boundaries.”

And in the 20th century, we’ve seen further blurrings or complications of personhood: “Corporations become legal persons, cars have personalities, and information wants to be free.” We’ve also seen the draining of that royal dignitas from offices, institutions, and collective representations of all sorts: belonging no longer confers meaning as it used to. We are in a “crisis of all of the institutional developments that replaced the image of the king as the defender of the weak against the strong, and, in their very development, made social life not only about the strong and the weak, but also about justice as fairness, and equality as the precondition for the pursuit of distinction.” These assumptions are decaying in every modern society.

Reed also suggests that, since the Cold War ended, America has returned to a pre-modern re-enchantment with the person of our president (as opposed to the office of the presidency): George W. Bush’s cowboy shtick shaping American response in Iraq; Obama’s race as a source of a liberal’s fantasy of healing racial wounds or a racist’s nightmare of usurpation; and of course Trump’s boorish ugly “authenticity.” And Trump now (like Orban, like Netanyahu) makes himself available for a kind of hero worship, founded on explicitly racial and nationalist appeals, that invites again a medieval “incorporation of the individual in the authority of the leader.” Bigots see themselves in Trump as medieval subjects saw themselves in their king, and this identification makes brutality against excluded persons easy.

Can this crisis be resolved? Reed, a sociology professor at UVa and a Jew, saw neo-Nazis marching out his window in 2017 chanting “Jews will not replace us.” The horrors of the last century are close by. He quotes political philosopher Danielle Allen in the wake of that spectacle: “The simple fact of the matter is that the world has never built a multiethnic democracy in which no particular ethnic group is in the majority and where political equality, social equality and economies that empower all have been achieved. We are engaged in a fight over whether to work together to build such a world.”

But can such a fight be won? “It is possible for popularly elected leaders to respect the authority of reformable institutions, for open societies to meet demands for equality and fairness, and for the rule of law to find its moral grounding in an ethically pluralistic society. It is even possible—though it has not yet been tried—that every single living individual can be recognized as sacred, and understood as a flourishing, inevitably contradictory, and wonderfully human author of action. But what is the language in which these possibilities for sacred dispensation will be articulated?” This is the crisis Reed names and leaves us twisting in. A leftist response might be that capitalism undermines the power of social tie and institution in any society it takes root in. Until it’s checked, both authoritarian nostalgia and social decay are inevitable. A conservative (or communitarian leftist) response might be that liberalism’s empowerment of the autonomous individual as the center of society ultimately leaves that individual plummeting through space: that a world where we’re all “king of our own castle” would be a place not of equality and fairness, but of total war.

*

13. Rachel Kushner, “Is Prison Necessary? Ruth Wilson Gilmore Might Change Your Mind.” This is the best article I’ve read in a mainstream publication on the philosophy of prison abolition. I wonder how many minds it changed? Gilmore, a lifelong activist and a scholar at CUNY, explains that “abolition means not just the closing of prisons but the presence, instead, of vital systems of support that many communities lack. Instead of asking how, in a future without prisons, we will deal with so-called violent people, abolitionists ask how we resolve inequalities and get people the resources they need long before the hypothetical moment when, as Gilmore puts it, they ‘mess up.'”

13. Rachel Kushner, “Is Prison Necessary? Ruth Wilson Gilmore Might Change Your Mind.” This is the best article I’ve read in a mainstream publication on the philosophy of prison abolition. I wonder how many minds it changed? Gilmore, a lifelong activist and a scholar at CUNY, explains that “abolition means not just the closing of prisons but the presence, instead, of vital systems of support that many communities lack. Instead of asking how, in a future without prisons, we will deal with so-called violent people, abolitionists ask how we resolve inequalities and get people the resources they need long before the hypothetical moment when, as Gilmore puts it, they ‘mess up.'”

Gilmore is also at pains to complicate some of the shorthand other activists use in discussing the carceral state. First, she says that mass incarceration is not about profit, but about the competition among state agencies for government revenue. “Under austerity, the social-welfare function shrinks; the agencies that receive the money are the police, firefighters and corrections. So other agencies start to copy what the police do: The education department, for instance, learns that it can receive money for metal detectors much more easily than it can for other kinds of facility upgrades. And prisons can access funds that traditionally went elsewhere — for example, money goes to county jails and state prisons for ‘mental health services’ rather than into public health generally.” The DOC isn’t an avaricious corporation, but an almost uniquely powerful lobby group that has captured the “surplus state capacity” of investors in public finance.

Gilmore also speaks of the violence and degradation of mass incarceration but disputes that it is “a modified continuation of slavery,” the uncompensated extraction of labor under threat of punishment. “The overwhelming problem for people inside prison,” she says, “is not that their labor is super exploited; it’s that they’re being warehoused with very little to do and not being given any kind of programs or resources that enable them to succeed once they do get out of prison.” Those incarcerated are “surplus labor,” carved out of the economy by urban deindustrialization and rural decay brought on (in California at least) by declining land values and lack of irrigation water. Until our economy is radically transformed, these people will remain an abandoned and abused surplus, whether behind bars or not. Gilmore argues that prison abolition is a structural, not an institutional, struggle, encompassing labor, wealth distribution, conflict resolution, racism, and the allocation of state dollars.

*

14. Shoutout to you for reading this far! Below, the true work of art speaks for itself:

2019: My Year in Music

Hi dear hearts, this comes to you late after a month of a broken computer, a thumb I split while splitting kindling, and some good deep hard work in my community and relationships that kept away from my beloved nerdy pleasures.

But so: here’s the music that kept me alive from this year, plus an accompanying playlist. As always, it includes some treasures from last year that I just now got to.

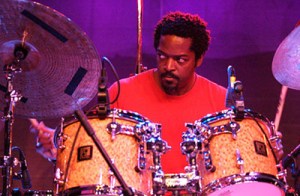

First thing is that this is a year that contemporary jazz really opened up for me with three very different records I adored. Steve Lehman’s The People I Love is presented as his tribute to the classic saxophone-quartet format, but the record starts out with a severity that I had to reach for my limited antecedents for: Dave Liebman’s scorching live show I saw in a big churchy stone space a decade ago with other slack-jawed grad students. Lehman’s playing is dextrous, fast-moving, and extreme; I love the conversations he locks into with digressive and tuneful pianist Craig Taborn on “qPlay” (dig too the skittering synthesized drums below it) and drummer Damion Reid on “Beyond All Limits.” Music about energy, not narrative; solos about dialogue, not commentary. (Lehman’s on Bandcamp, but not on Spotify.) I also loved the Marta Sanchez Quintet’s El Rayo de Luz; Sanchez’s sense of harmony in her horn charts is eerie and exquisite, and the music’s emotional center is in the way the piano will answer, tug at, twist up, and return a melody back to her two saxophonists: it’s subtle, brainy, tender. It makes my ribcage ache. For presence and aural pleasure, I love Gerald Cleaver’s Live at Firehouse 12: again, the limitations of my listening history don’t leave me much to draw on, but I love that jazz-drummer thing of keeping the beat and commenting on it at once, riffing back to his soloists or shifting suddenly under them and forcing them to duck after him. The piano is mixed low: the attention is much less on underlying chordal structure than on all on the ideas Cleaver tosses up to his horns and gets tossed back. The horns’ melodies are sometimes twisty, sometimes downright jolly: the climax of “Detroit” is as polyphonic as Dixieland.

First thing is that this is a year that contemporary jazz really opened up for me with three very different records I adored. Steve Lehman’s The People I Love is presented as his tribute to the classic saxophone-quartet format, but the record starts out with a severity that I had to reach for my limited antecedents for: Dave Liebman’s scorching live show I saw in a big churchy stone space a decade ago with other slack-jawed grad students. Lehman’s playing is dextrous, fast-moving, and extreme; I love the conversations he locks into with digressive and tuneful pianist Craig Taborn on “qPlay” (dig too the skittering synthesized drums below it) and drummer Damion Reid on “Beyond All Limits.” Music about energy, not narrative; solos about dialogue, not commentary. (Lehman’s on Bandcamp, but not on Spotify.) I also loved the Marta Sanchez Quintet’s El Rayo de Luz; Sanchez’s sense of harmony in her horn charts is eerie and exquisite, and the music’s emotional center is in the way the piano will answer, tug at, twist up, and return a melody back to her two saxophonists: it’s subtle, brainy, tender. It makes my ribcage ache. For presence and aural pleasure, I love Gerald Cleaver’s Live at Firehouse 12: again, the limitations of my listening history don’t leave me much to draw on, but I love that jazz-drummer thing of keeping the beat and commenting on it at once, riffing back to his soloists or shifting suddenly under them and forcing them to duck after him. The piano is mixed low: the attention is much less on underlying chordal structure than on all on the ideas Cleaver tosses up to his horns and gets tossed back. The horns’ melodies are sometimes twisty, sometimes downright jolly: the climax of “Detroit” is as polyphonic as Dixieland.

Two jazz reissues this year I also loved: the rangy small-group playing of Charles Mingus’s Jazz in Detroit, recorded live (with accompanying interviews) at a short-lived collective space, the Strata, in 1973. After the fun gigantism of his big-band comeback, Let My People Hear Music, Mingus seemed to be in the mood for exploring wider spaces with a smaller group: his players here are all young, some new to playing with him, and they all stretch. By contrast, Eric Dolphy’s Musical Prophet: the Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions feels not like rovings but like musings. Dolphy’s playing could be fiery-intense and rough and there are a few big full-band tunes, but for most of these recordings, Dolphy seems to deliberately downplay forward motion: instead, the music keeps collapsing into self-reflection, irony, melancholy (“Come Sunday”‘s moaning bass floating alongside Dolphy’s murmuring bari sax), buried self-assertion (the theme of “Alone Together” doesn’t fully show up until 12 minutes of musical conversation between Dolphy and his bassist), and a cerebral exploratory quality held up by an inexhaustible melodic creativity. Dolphy contained multitudes; he died of undiagnosed diabetes less than a year after these recordings. How many other jazz musicians died of health conditions aggravated by structural racism?

Two jazz reissues this year I also loved: the rangy small-group playing of Charles Mingus’s Jazz in Detroit, recorded live (with accompanying interviews) at a short-lived collective space, the Strata, in 1973. After the fun gigantism of his big-band comeback, Let My People Hear Music, Mingus seemed to be in the mood for exploring wider spaces with a smaller group: his players here are all young, some new to playing with him, and they all stretch. By contrast, Eric Dolphy’s Musical Prophet: the Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions feels not like rovings but like musings. Dolphy’s playing could be fiery-intense and rough and there are a few big full-band tunes, but for most of these recordings, Dolphy seems to deliberately downplay forward motion: instead, the music keeps collapsing into self-reflection, irony, melancholy (“Come Sunday”‘s moaning bass floating alongside Dolphy’s murmuring bari sax), buried self-assertion (the theme of “Alone Together” doesn’t fully show up until 12 minutes of musical conversation between Dolphy and his bassist), and a cerebral exploratory quality held up by an inexhaustible melodic creativity. Dolphy contained multitudes; he died of undiagnosed diabetes less than a year after these recordings. How many other jazz musicians died of health conditions aggravated by structural racism?

The mood of our big quiet hemlocks and swift icy creek are caught by Emily A. Sprague’s Water Memory, a beautiful ambient project from a musician best known in her singer-songwriter work as Florist. Sprague doesn’t wear down listeners’ distinct attention under reverb or drones: instead, each instrument is a small clearly-rendered organism– or a small repeated movement, like the flickering of a flagellum, inside an organism– and the songs’ colors vary across the album. A meeting with a perfect musical creature in 40-plus minutes.

The mood of our big quiet hemlocks and swift icy creek are caught by Emily A. Sprague’s Water Memory, a beautiful ambient project from a musician best known in her singer-songwriter work as Florist. Sprague doesn’t wear down listeners’ distinct attention under reverb or drones: instead, each instrument is a small clearly-rendered organism– or a small repeated movement, like the flickering of a flagellum, inside an organism– and the songs’ colors vary across the album. A meeting with a perfect musical creature in 40-plus minutes.

I absolutely can’t get enough of Jamila Woods’s LEGACY! LEGACY!, an album of subtly shifting influences and musical colors, driven by Woods’s arching twisting sense of vocal melody. She’s a queenly, sharp presence (“shut up motherfucker, I don’t take requests”), and her sense of pride stretches way back– her companions and lovers and “holy books” are all drawn from way back, from a deep sense of musical and communal history. I especially treasure the little skirls of jazzy guitar on “BASQUIAT” and the soothing-then-strutting two-part “GIOVANNI.” Also word to Earl Sweatshirt’s Some Rap Songs, out at some extreme where hip-hop meets avant-garde jazz and experimental poetry; Earl may still be in his Xany-gnashing, Caddy-smashing youth but he’s making a world of his own around it if so. My bangers of the year were Lizzo’s “Tempo,” with the inexhaustible and self-possessed Missy Elliott, and Normani’s perfect “Motivation,” who I first heard alongside Doja Cat, thank you Sayer for introducing me. Let’s take a moment too and be grateful for how much good pop there is right now about easy, confident pleasure in material flash or in guilt-free, un-power-tripping free-agent-type sex: if you want to, it’s easy to avoid bellows of lost entitlement, emotional blackmail, stray shots or empty bottles and stay in the Top 40. Oh and I give up, I also loved Katy Perry’s “Never Really Over.”

I absolutely can’t get enough of Jamila Woods’s LEGACY! LEGACY!, an album of subtly shifting influences and musical colors, driven by Woods’s arching twisting sense of vocal melody. She’s a queenly, sharp presence (“shut up motherfucker, I don’t take requests”), and her sense of pride stretches way back– her companions and lovers and “holy books” are all drawn from way back, from a deep sense of musical and communal history. I especially treasure the little skirls of jazzy guitar on “BASQUIAT” and the soothing-then-strutting two-part “GIOVANNI.” Also word to Earl Sweatshirt’s Some Rap Songs, out at some extreme where hip-hop meets avant-garde jazz and experimental poetry; Earl may still be in his Xany-gnashing, Caddy-smashing youth but he’s making a world of his own around it if so. My bangers of the year were Lizzo’s “Tempo,” with the inexhaustible and self-possessed Missy Elliott, and Normani’s perfect “Motivation,” who I first heard alongside Doja Cat, thank you Sayer for introducing me. Let’s take a moment too and be grateful for how much good pop there is right now about easy, confident pleasure in material flash or in guilt-free, un-power-tripping free-agent-type sex: if you want to, it’s easy to avoid bellows of lost entitlement, emotional blackmail, stray shots or empty bottles and stay in the Top 40. Oh and I give up, I also loved Katy Perry’s “Never Really Over.”

I looked forward to a dozen-plus indie rock albums this year but wound up adoring only a few. Frankie Cosmos’s Close It Quietly is Greta Kline’s absolute best work so far, a work on tip-toe balance between assertion and minimalism, small acts of emotional courage and small touches of self-deprecating humor. Kline’s songs are mostly tiny, so when she repeats a chorus (as on “So Blue”) you really feel it, and when a hook kicks in (as in the B section of “Rings [on a Tree]”) it hits you right in the shoulders. Laura Stevenson’s The Big Freeze is finally a whole album of hers I’ve loved as much as I loved 2012’s single “Runner.” But where that song’s dynamism and surge thrilled me, Freeze is more austere and spacious: it’s a big roomy recording of overdriven electric, fingerpicked acoustic guitar and an underlining of low harmony. Its sound reminds me of Brian Paulson’s groundbreaking production on Spiderland, letting distorted and acoustic instruments speak to each other without violence. I also loved (Sandy) Alex G’s House of Sugar. Alex Giannascoli’s earlier records were characterized by a lo-fi slacker shrug that, when pushed, stiffened into open resistance. He’d blast off synth rackets, snip songs short just as they took off, process instruments through a tin can. The musical ingredients on House of Sugar have evened out a little: the listener can expect close-mic’d and often double-tracked acoustic guitar, hanging looped-up synthesizers, violin, far-off wailing or pitch-shifted backing vocals, some nostalgic sax, and a fake accent or two, not easy but not self-undermining either. There’s a self-enclosed musical richness to these arrangements and a good-enough-for-me roughness that’s belied by the pathos and grief of the lyrics; Giannascoli is absolutely soaked in a fear of death and split by gender-ambiguous heartbreak. Most lo-fi albums feel smaller as they go on; House of Sugar widens instead into something big and melancholy.

I looked forward to a dozen-plus indie rock albums this year but wound up adoring only a few. Frankie Cosmos’s Close It Quietly is Greta Kline’s absolute best work so far, a work on tip-toe balance between assertion and minimalism, small acts of emotional courage and small touches of self-deprecating humor. Kline’s songs are mostly tiny, so when she repeats a chorus (as on “So Blue”) you really feel it, and when a hook kicks in (as in the B section of “Rings [on a Tree]”) it hits you right in the shoulders. Laura Stevenson’s The Big Freeze is finally a whole album of hers I’ve loved as much as I loved 2012’s single “Runner.” But where that song’s dynamism and surge thrilled me, Freeze is more austere and spacious: it’s a big roomy recording of overdriven electric, fingerpicked acoustic guitar and an underlining of low harmony. Its sound reminds me of Brian Paulson’s groundbreaking production on Spiderland, letting distorted and acoustic instruments speak to each other without violence. I also loved (Sandy) Alex G’s House of Sugar. Alex Giannascoli’s earlier records were characterized by a lo-fi slacker shrug that, when pushed, stiffened into open resistance. He’d blast off synth rackets, snip songs short just as they took off, process instruments through a tin can. The musical ingredients on House of Sugar have evened out a little: the listener can expect close-mic’d and often double-tracked acoustic guitar, hanging looped-up synthesizers, violin, far-off wailing or pitch-shifted backing vocals, some nostalgic sax, and a fake accent or two, not easy but not self-undermining either. There’s a self-enclosed musical richness to these arrangements and a good-enough-for-me roughness that’s belied by the pathos and grief of the lyrics; Giannascoli is absolutely soaked in a fear of death and split by gender-ambiguous heartbreak. Most lo-fi albums feel smaller as they go on; House of Sugar widens instead into something big and melancholy.

I spent a week of evenings in the kitchen getting electrocuted by Mannequin Pussy’s Patience, an album of romantic longing, heartsickness, and rage all together, and a lot of drives with the New Pornographers’ In the Morse Code of the Brakelights. Brakelights is an album dominated by gigantism: cliffs of big bright reverby guitar, abrupt bangs of processed snares, melodies impossible to trace as lines of overlapping gray mountains, strings and ah-ah-ahs that swoop by like mountain wind. A.C. Newman is the last songwriter left in the group, and he’s stayed cerebral as he’s aged: he’s not particularly heated, cynical, disillusioned, etc.; he writes more about patterns of relationship than about relationships. I guess this is one way to age contentedly. Please also do not neglect the stunning big kingdom of Helen America’s Red Sun. One-off songs I loved this year: Pedro the Lion’s “Clean Up,” Big Thief’s “Cattails,” Black Ends’ “Sellout” (a freaky math-rock jam from my favorite new Seattle band), Jay Som’s “Tenderness” (though also shoutout to “Superbike” and “Devotion”: Melina Duterte’s guest-packed ensemble playing evoked less personality than she did playing every instrument on Everybody Works, but the gleaming compressed guitar and her small turned-inward voice are still a pleasure everywhere in her music), and Priests’ “I’m Clean,” an arch and nervy kiss-off that helps me feel human and brave when I need it.

I spent a week of evenings in the kitchen getting electrocuted by Mannequin Pussy’s Patience, an album of romantic longing, heartsickness, and rage all together, and a lot of drives with the New Pornographers’ In the Morse Code of the Brakelights. Brakelights is an album dominated by gigantism: cliffs of big bright reverby guitar, abrupt bangs of processed snares, melodies impossible to trace as lines of overlapping gray mountains, strings and ah-ah-ahs that swoop by like mountain wind. A.C. Newman is the last songwriter left in the group, and he’s stayed cerebral as he’s aged: he’s not particularly heated, cynical, disillusioned, etc.; he writes more about patterns of relationship than about relationships. I guess this is one way to age contentedly. Please also do not neglect the stunning big kingdom of Helen America’s Red Sun. One-off songs I loved this year: Pedro the Lion’s “Clean Up,” Big Thief’s “Cattails,” Black Ends’ “Sellout” (a freaky math-rock jam from my favorite new Seattle band), Jay Som’s “Tenderness” (though also shoutout to “Superbike” and “Devotion”: Melina Duterte’s guest-packed ensemble playing evoked less personality than she did playing every instrument on Everybody Works, but the gleaming compressed guitar and her small turned-inward voice are still a pleasure everywhere in her music), and Priests’ “I’m Clean,” an arch and nervy kiss-off that helps me feel human and brave when I need it.

A PS for the truly riveted: here are the older albums I’ve completely fallen for this year: Donato Dozzy’s K, Fiona Apple’s Idler Wheel, Jonathan Richman’s Action Packed compilation, lots and lots and lots of 80s and 90s dancehall reggae, Bach’s violin sonatas and partitas, Schubert’s piano sonatas, Team Dresch, Joe Lovano’s I’m All for You, Hank Jones’s The Trio (the 1978 one), the Spinanes’ Manos, PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me, Orchestre Baobab’s Made in Dakar, Mingus’s big-band record Let My Children Hear Music, Arthur Blythe’s Lenox Avenue Breakdown, John Prine’s Sweet Revenge and Storm Windows, Velocity Girl’s first compilation and Copacetic, Al Green’s I’m Still in Love with You, Dave Edmunds’s Repeat When Necessary, Bonnie Raitt, Luther Vandross’s compilation The Best of Luther Vandross… The Best of Love, Emmylou Harris’s Roses in the Snow, George Jones’s All Time Greatest Hits Vol. 1, John Fahey’s Of Rivers and Religion, Teddy Pendergrass’s TP, Pharoah Sanders’ Message from Home (produced by the mighty Bill Laswell), the Fastbacks’ Answer the Phone, Dummy, Sonny Rollins’s Sonny Plus 4 (his first album as a bandleader, the final studio recording Clifford Brown made before his death), Miles Davis’s 70s electric albums Black Beauty and Big Fun, the many treasures of Gary Giddins’ two-part “Post-War Jazz: an Arbitrary Roadmap,” The Indestructible Beat of Soweto, Vol. 4: Kings and Queens of Township Jive, and— on the turntable right now— The “King” Kong Compilation collecting Leslie Kong’s pioneering early reggae productions.

Comments Off on 2019: My Year in Music

Filed under music

The Ten Best Things on the Internet: February 2019

10. The opera teacher Salvatore Fisichella’s master class with tenor Andrew Owens: when Cait showed this to me, she said, “This is why I hope humans don’t go extinct.” I don’t understand more than few phrases of what he’s saying but when his (very famous!) student gets it right, I feel it too.

9. Moira Donegan, “Sex During Wartime: the return of Andrea Dworkin’s radical vision.” In college, I knew from my radical friends to dislike and disparage Andrea Dworkin, the unfun dogmatic anti-porn scold, without having read more than a few pages. But ideas central to her work are now being shone back to our larger culture, and I was very grateful for Moira Donegan’s reflection on Last Days at Hot Slit, a new selection of her work. Donegan, summarizing Dworkin’s thinking, writes that “[rape is] not an anomaly, but the fulfillment of a foundational cultural narrative. Rape is not exceptional but common, committed by common men acting on common assumptions about who men are and what women are.” Male power-over, our reduction of women to compliant or brutalized objects, for Dworkin prefigured all other forms of oppression and societal violence; but Dworkin also remained intersectional in her thinking, advocating for accessible trans healthcare and charging middle-class white women to reject the false comforts of their relative privilege to stand alongside, and support, women of color and poor women. And what is the spiritual work of men in undoing the antagonism, humiliation, and violence we’re taught to apply to women? In 1983, she addressed a male audience: “Have you ever wondered why we are not just in armed combat against you? It’s not because there’s a shortage of kitchen knives in this country. It is because we believe in your humanity, against all the evidence.” Can we men imagine and work for a world where non-men are equal historical selves? Our humanity depends on it.

9. Moira Donegan, “Sex During Wartime: the return of Andrea Dworkin’s radical vision.” In college, I knew from my radical friends to dislike and disparage Andrea Dworkin, the unfun dogmatic anti-porn scold, without having read more than a few pages. But ideas central to her work are now being shone back to our larger culture, and I was very grateful for Moira Donegan’s reflection on Last Days at Hot Slit, a new selection of her work. Donegan, summarizing Dworkin’s thinking, writes that “[rape is] not an anomaly, but the fulfillment of a foundational cultural narrative. Rape is not exceptional but common, committed by common men acting on common assumptions about who men are and what women are.” Male power-over, our reduction of women to compliant or brutalized objects, for Dworkin prefigured all other forms of oppression and societal violence; but Dworkin also remained intersectional in her thinking, advocating for accessible trans healthcare and charging middle-class white women to reject the false comforts of their relative privilege to stand alongside, and support, women of color and poor women. And what is the spiritual work of men in undoing the antagonism, humiliation, and violence we’re taught to apply to women? In 1983, she addressed a male audience: “Have you ever wondered why we are not just in armed combat against you? It’s not because there’s a shortage of kitchen knives in this country. It is because we believe in your humanity, against all the evidence.” Can we men imagine and work for a world where non-men are equal historical selves? Our humanity depends on it.

8. A cheat/double: a special shoutout to bad reviews. Most big juicy bad reviews are fun but pointless— critics implicitly flattering their own taste, giving themselves over to purple writing whose insults aren’t as evocative as they think they are. Youngish critics, in their bad reviews, tend toward an overstated outrage at the violation of their precious sensibility; oldish critics in their bad reviews turn “shrill and stale at once” (James Wood on Harold Bloom), pounding at the same advancing targets long past anyone caring. Both types of reviews are fun are fun to nibble on and have next to zero shelf life.

But there are exceptions. Literary critic Andrea Long Chu reviews Jill Soloway’s way-acclaimed memoir She Wants It, on Soloway’s self-discovery as a director and her work creating the TV show Transparent. Chu’s tone is a measured disbelief at the narcissism, sloppiness, and vacuity she finds in Soloway’s book. In Soloway, Long Chu writes, “one finds the worst of grandiose Seventies-era conceits about the transformative power of the avant-garde guiltlessly hitched to a yogic West Coast startup mindset”; on Soloway’s own performance of identity, Chu writes that “all we need remember is that being trans because you want the attention doesn’t make you ‘not really’ trans; it just makes you annoying”; as to the book’s damage-control subtext, Chu decides that “Jill Soloway has an unstoppable, pathological urge to tell on herself.”

But there are exceptions. Literary critic Andrea Long Chu reviews Jill Soloway’s way-acclaimed memoir She Wants It, on Soloway’s self-discovery as a director and her work creating the TV show Transparent. Chu’s tone is a measured disbelief at the narcissism, sloppiness, and vacuity she finds in Soloway’s book. In Soloway, Long Chu writes, “one finds the worst of grandiose Seventies-era conceits about the transformative power of the avant-garde guiltlessly hitched to a yogic West Coast startup mindset”; on Soloway’s own performance of identity, Chu writes that “all we need remember is that being trans because you want the attention doesn’t make you ‘not really’ trans; it just makes you annoying”; as to the book’s damage-control subtext, Chu decides that “Jill Soloway has an unstoppable, pathological urge to tell on herself.”

And an ever-relevant good oldie: Eugene McCarraher, a history professor at Villanova, produced what’s still my favorite critical response to the New Atheism, a scrupulous dismantling of Christopher Hitchens’ God Is Not Great called “This Book Is Not Good.” I went back to McCarraher’s essay after reading John Gray’s Seven Types of Atheism, curious to see if I still loved it, and boy I do. Hitchens’ book, McCarraher says, is a “haute middlebrow tirade” that has nothing insightful or honest to say about theology, philosophy, or history and is fed by “a gooey compound of boosterish bromides and liberal nationalism.” As to a dreamt-of world free of religion, Hitchens’ moral imagination sees only “in terms of professional and managerial expertise,” a world given over to technocratic bosses who are in reality every bit as capable of obfuscation, domination, violence, and backwardness as theocratic states. Our war in Iraq, McCarraher says, should show us the brutality and ideological folly our secular, capitalist state is capable of; Hitchens’ delighted assurance in the virtue of that very war sickens him.

And an ever-relevant good oldie: Eugene McCarraher, a history professor at Villanova, produced what’s still my favorite critical response to the New Atheism, a scrupulous dismantling of Christopher Hitchens’ God Is Not Great called “This Book Is Not Good.” I went back to McCarraher’s essay after reading John Gray’s Seven Types of Atheism, curious to see if I still loved it, and boy I do. Hitchens’ book, McCarraher says, is a “haute middlebrow tirade” that has nothing insightful or honest to say about theology, philosophy, or history and is fed by “a gooey compound of boosterish bromides and liberal nationalism.” As to a dreamt-of world free of religion, Hitchens’ moral imagination sees only “in terms of professional and managerial expertise,” a world given over to technocratic bosses who are in reality every bit as capable of obfuscation, domination, violence, and backwardness as theocratic states. Our war in Iraq, McCarraher says, should show us the brutality and ideological folly our secular, capitalist state is capable of; Hitchens’ delighted assurance in the virtue of that very war sickens him.

7. Our president, wayward and flatterable, has wandered off from his own stated intent to withdraw troops from Syria. Too bad. But Matt Taibbi’s piece in Rolling Stone on the planned withdrawal is still outstanding. Taibbi describes the outrage Trump’s decision drew from our two war parties, and he captures the absolute mind-boggling scope of our venality, violence, and never-ending military mission drift in the Middle East. It can be easy for those of us resisting imperialism to assume our enemies are cunning and all-powerful. It’s not true. Read Taibbi to be reminded just how dumb empire can be. (See also this essay from a genuine conservative on the credulousness and bullying self-importance of two extremely famous pro-war #nevertrumpers.)

6. Obsessed— obsessed obsessed obsessed— with Tierra Whack’s 15-minute, 15-song music video.

5. Journalist Jesse Singal, with Freddie de Boer’s permission, returns to online availability three of de Boer’s bombthrowing essays on the state of Left cultural and academic discourse. I don’t agree with everything in these essays, but de Boer’s moral rage at the left’s internalization of cop culture– what Sarah Schulman would call the equating of conflict with an existential assault, complete with a pile-on on the offender led by a mob of virtuous citizens— is a tonic.

4. Just how much does it cost to call out love-and-light good-vibes spiritual thinkers for their ignorance of racism, persistent inequality, and state violence? Black Muslim feminist spiritual educator Layla F. Saad answers: “I Need to Talk to Spiritual White Women about White Supremacy” part 1 and part 2. The culture industry Saad identifies is associated with female entrepeneurs, but the apothecary-nice-guy subculture is just as guilty of checking out, repeating platitudes, and getting ugly when confronted. Dig the workbook on Saad’s main site too.

4. Just how much does it cost to call out love-and-light good-vibes spiritual thinkers for their ignorance of racism, persistent inequality, and state violence? Black Muslim feminist spiritual educator Layla F. Saad answers: “I Need to Talk to Spiritual White Women about White Supremacy” part 1 and part 2. The culture industry Saad identifies is associated with female entrepeneurs, but the apothecary-nice-guy subculture is just as guilty of checking out, repeating platitudes, and getting ugly when confronted. Dig the workbook on Saad’s main site too.

3. Lindsay Zoladz is one of my favorite music critics, a brainy and nimble writer who can set a scene in just a few sentences and who’s unafraid to fan out on her loves; her “December Boy: on Alex Chilton” taught me a lot about the lost years of this mercurial genius and reminded me of what I freaking love about Big Star. Growing up weird in a Navy town, my 12-year-old self found in indie music the immense relief of knowing my sensibility wasn’t alone. But most of what I found– John Fahey, Kate Bush, Aphex Twin, Husker Du, Sleater-Kinney, the Velvet Underground– wasn’t remotely utopian. These temperaments had survived, but they didn’t have an imagined better world out there to point me to. Big Star felt different: what was so cool about Big Star’s first two records was how they posited a whole alternate adolescence. In their music I could hang out, fall into a crush, break up, get my ears blasted in the backseat, watch the sunrise.

3. Lindsay Zoladz is one of my favorite music critics, a brainy and nimble writer who can set a scene in just a few sentences and who’s unafraid to fan out on her loves; her “December Boy: on Alex Chilton” taught me a lot about the lost years of this mercurial genius and reminded me of what I freaking love about Big Star. Growing up weird in a Navy town, my 12-year-old self found in indie music the immense relief of knowing my sensibility wasn’t alone. But most of what I found– John Fahey, Kate Bush, Aphex Twin, Husker Du, Sleater-Kinney, the Velvet Underground– wasn’t remotely utopian. These temperaments had survived, but they didn’t have an imagined better world out there to point me to. Big Star felt different: what was so cool about Big Star’s first two records was how they posited a whole alternate adolescence. In their music I could hang out, fall into a crush, break up, get my ears blasted in the backseat, watch the sunrise.

2. Who was King writing to in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”? Broderick Greer gives the answer, quoting from “A Call for Unity,” the 1963 letter from white Alabama clergymen who sympathize with civil rights protestors’ “natural impatience” but call their continued direct actions, demonstrations, and protests “unwise and untimely.” King’s letter, smuggled from his cell, is his reply. The voice of the sensible middle never, ever changes. More and more I think of social justice work in terms of strategic radicalism: not “how can we reach across the aisle to create a compromise that will satisfy everyone,” but “how can we tactically force our sorta-allies in the middle to join our moral stand against what we find intolerable”?

2. Who was King writing to in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”? Broderick Greer gives the answer, quoting from “A Call for Unity,” the 1963 letter from white Alabama clergymen who sympathize with civil rights protestors’ “natural impatience” but call their continued direct actions, demonstrations, and protests “unwise and untimely.” King’s letter, smuggled from his cell, is his reply. The voice of the sensible middle never, ever changes. More and more I think of social justice work in terms of strategic radicalism: not “how can we reach across the aisle to create a compromise that will satisfy everyone,” but “how can we tactically force our sorta-allies in the middle to join our moral stand against what we find intolerable”?

1. And: live your best 1:14 by watching this clip of King on the origins of entrenched racial inequality, and the sole demand that will undo it. I showed this one to Finn.

2018: the Year in Music

This is the music that got me through the year, that disrupted or seized or soothed me. As always, includes a few records from the previous year I came to late.

This year the instrumental music I’ve loved best has foregrounded somatic emotional experience, bodily sensation. I absolutely cannot get enough of PAN’s compilation Mono No Aware: it’s ambient music that foregrounds not concepts or memory-qualities but big feelings and strong transformations. Its songs can be as hot and close as tears, as intimate as a lover pressed up against you, or as creepy as feeling yourself grow hooves or wings. Some of the textures/moods near the middle are too extreme and abrasive for me to do anything else to but listen, but that’s its own kind of ambience.

This year the instrumental music I’ve loved best has foregrounded somatic emotional experience, bodily sensation. I absolutely cannot get enough of PAN’s compilation Mono No Aware: it’s ambient music that foregrounds not concepts or memory-qualities but big feelings and strong transformations. Its songs can be as hot and close as tears, as intimate as a lover pressed up against you, or as creepy as feeling yourself grow hooves or wings. Some of the textures/moods near the middle are too extreme and abrasive for me to do anything else to but listen, but that’s its own kind of ambience.

Speaking of bodily pleasure, Four Tet‘s New Energy, especially “Scientists,” is a further step in a good direction for Kieran Hebden, away from the skittering nerves of his first few records, toward a beating heart and a sense of collective ecstasy: there are at least two or three other songs on this record that are on my permanent dance playlist. Jazz drummer Makaya McCraven’s Universal Beings (tied for my favorite record of the year) is body-music too. It’s some of the most rich and joyful ensemble playing I’ve heard in a long time, each of its four sides–London, New York, Chicago, LA–edited from popup studios and live jams into a distinct mood. Side two, knotting itself into the breathless “Atlantic Black” (Tomeka Reid and Shabaka Hutchings twisting and feeding off each other) is the funkiest and my favorite, but each has an everything-here-now urgency, even when the soloists play harp or cello. I’ve loved to go back to again and again. A smaller-scale pleasure has the been the totally out-of-the-box improvised duet/duel from pianist Irene Schweizer and drummer Joey Baron on Live! This record is gymnastic, violent, childlike, playful, and exhilarating.

Speaking of bodily pleasure, Four Tet‘s New Energy, especially “Scientists,” is a further step in a good direction for Kieran Hebden, away from the skittering nerves of his first few records, toward a beating heart and a sense of collective ecstasy: there are at least two or three other songs on this record that are on my permanent dance playlist. Jazz drummer Makaya McCraven’s Universal Beings (tied for my favorite record of the year) is body-music too. It’s some of the most rich and joyful ensemble playing I’ve heard in a long time, each of its four sides–London, New York, Chicago, LA–edited from popup studios and live jams into a distinct mood. Side two, knotting itself into the breathless “Atlantic Black” (Tomeka Reid and Shabaka Hutchings twisting and feeding off each other) is the funkiest and my favorite, but each has an everything-here-now urgency, even when the soloists play harp or cello. I’ve loved to go back to again and again. A smaller-scale pleasure has the been the totally out-of-the-box improvised duet/duel from pianist Irene Schweizer and drummer Joey Baron on Live! This record is gymnastic, violent, childlike, playful, and exhilarating.

Speaking of timbre, I had to love it as a lullaby first but I’ve come around to Yo La Tengo’s sleepy subtle new record, There’s a Riot Going On: I couldn’t pay any direct attention to it on its first few plays but its presence has stayed with me, a blanket I can always crawl under even as the lyrics suggest uncertainty, dread, the brevity and fragility of consolation. And then songs started coming out of the sound: “Forever,” “Polynesia #1,” “Let’s Do It Wrong,” “For You Too.” I similarly took awhile to love the new Ought, Room inside the World. I was puzzled and put off by the polish and spaciousness of the production after loving by the loose wires and crumpled metal of Sun Coming Down, but that smooth coating covers some good medicine and Tim Darcy, writing gorgeous lyrics I like even better than his old taunting chants or aspirational cries, still sings like someone clowning on Jimmy Stewart. They’re growing into grandeur.

Speaking of timbre, I had to love it as a lullaby first but I’ve come around to Yo La Tengo’s sleepy subtle new record, There’s a Riot Going On: I couldn’t pay any direct attention to it on its first few plays but its presence has stayed with me, a blanket I can always crawl under even as the lyrics suggest uncertainty, dread, the brevity and fragility of consolation. And then songs started coming out of the sound: “Forever,” “Polynesia #1,” “Let’s Do It Wrong,” “For You Too.” I similarly took awhile to love the new Ought, Room inside the World. I was puzzled and put off by the polish and spaciousness of the production after loving by the loose wires and crumpled metal of Sun Coming Down, but that smooth coating covers some good medicine and Tim Darcy, writing gorgeous lyrics I like even better than his old taunting chants or aspirational cries, still sings like someone clowning on Jimmy Stewart. They’re growing into grandeur.

It’s so easy to tap through on Spotify, try the next of the million flavors, that I have to browse new music in a way that’s less attentive but more feel-sensitive if I want anything to sink in or spur a response for me: when I browse, it’s not for argument but for appetite. Popping out in a long shuffle, Maximum Joy‘s glorious new reissue (seven singles on four sides of vinyl) I Can’t Stand Here on Quiet Nights was delicious right away– spaceyness and heavy bottom of the dub bass, kiddish chanting of Janine Rainforth, spikes of guitar. There’s a sense of communitarianism, utopian hope, in the music’s borrowings and interpolations (reggae, shrieks, guitar jangle, dumb squawking sax) that makes me think of second-wave ska or African Head Charge, defiant of its desperately bleak, individualist political moment of England in the early 80s.